Tranching Your Emergency Fund

Table of Contents

Photo by Alexandra Khudyntseva on Unsplash

What is an Emergency Fund?

An emergency fund is a pool of money to draw on in emergencies allowing you you to absorb unforeseen expenses or gaps in regular income.

The first step is putting 3-6 months of expenses into some sort of liquid, low risk account. The traditional advice has been to open a “high yield” FDIC insured checking or savings account at a bank or credit union. All of these accounts are liquid, safe, and can provide funds within a few days.

A Brief History of Real Bank Account Yields

Note: While there are technical differences between “high yield” checking and savings accounts, I will refer to them as “bank accounts” going forward for brevity.

Until February 2022, these accounts yielded up to ~2% interest annually. During this period, if you received 2% APY, inflation was ~2.5%, and your effective tax rate was around 30%, you were only losing 1.1% of the value of the account per year.

As an example, if you had $10,000, and left that money in an account for 10 years, you would have nominal value of $12,190, and the equivalent of $8,977 after accounting for taxes and inflation.

Net Effects of Taxes + Inflation Over 10 Years

| Year | Total balance | Balance net taxes | Value net taxes and inflation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $10,200 | $10,140 | $9,893 |

| 2 | $10,404 | $10,282 | $9,787 |

| 3 | $10,612 | $10,426 | $9,681 |

| 4 | $10,824 | $10,572 | $9,578 |

| 5 | $11,041 | $10,720 | $9,475 |

| 6 | $11,262 | $10,870 | $9,373 |

| 7 | $11,487 | $11,022 | $9,273 |

| 8 | $11,717 | $11,176 | $9,173 |

| 9 | $11,951 | $11,333 | $9,075 |

| 10 | $12,190 | $11,492 | $8,977 |

Assumptions: $10,000 single lump sum @ 2% APY, inflation 2.5%, 30% effective tax rate

Overall it would “cost” you $1023 in purchasing power over ten years, or $102.30 a year to keep this money liquid and safe. This is essentially an insurance “premium” you “pay” to yourself to provide protection from unexpected expenses. This is not a bad deal considering the nominal “cost” given the requirements for an emergency fund account.

Emergency Funds in the Age of Inflation

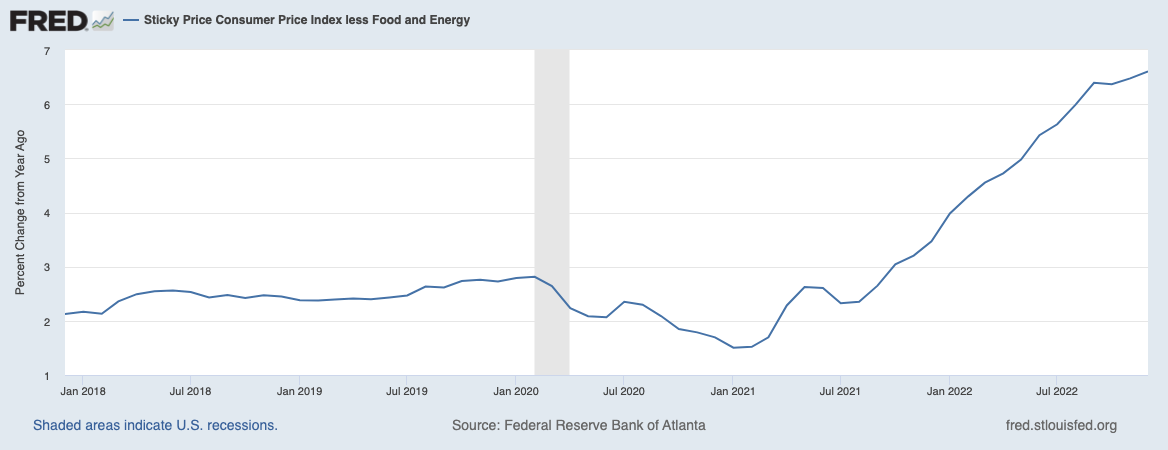

As inflation began to climb in August 2020, suddenly your purchasing power was deteriorating at a rate not seen since the early 1970s. Now you were paying an increasing “premium” for keeping this pool of money in a bank as the delta between the APY and inflation increased month over month.

As of publication, most online banks are offering up to 3.3% APY. Smaller players are offering up to 4% with some monthly requirements (credit card spend minimum, direct deposit minimum). Inflation is currently running around 6.89%.

This means that by the most conservative measures you’re losing 2.89% of your purchasing power before taxes, and closer to ~4% after (30% effective tax rate). So by this measure, you’re losing 3 times more purchasing power in the same time period as you were in early 2020.

| Year | Total balance | Balance net taxes | Value net taxes and inflation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $10,400 | $10,280 | $9,617 |

| 2 | $10,816 | $10,568 | $9,249 |

| 3 | $11,249 | $10,864 | $8,895 |

| 4 | $11,699 | $11,168 | $8,555 |

| 5 | $12,167 | $11,481 | $8,228 |

| 6 | $12,653 | $11,802 | $7,913 |

| 7 | $13,159 | $12,133 | $7,610 |

| 8 | $13,686 | $12,472 | $7,319 |

| 9 | $14,233 | $12,821 | $7,039 |

| 10 | $14,802 | $13,180 | $6,770 |

Assumptions: $10,000 single lump sum @ 4% APY, inflation 6.89%, 30% effective tax rate

Comparatively, it would “cost” you $3230 in purchasing power over ten years after taxes and inflation, or the equivalent “premium” of $323 a year.

With that said, there are alternatives to keeping an emergency fund in a bank account.

Emergency Fund, meet I Bonds

I bonds can serve as a part of your emergency fund allocation. I bonds provide inflation indexed yields and are used to reduce the impact on your purchasing power if you have access to them. Some caveats:

- Must be a US citizen or resident.

- You can purchase up to $10,000 worth in a calendar year.

- All purchased bonds cannot be redeemed for 12 months from purchase date.

- Any redemptions within 5 years of purchase forfeit 3 months worth of interest.

I bond yields were not all that enticing between 2015-2019. In many cases you could get higher post-tax yields by just parking cash in a high yield bank account.

They became really interesting when inflation quickly surpassed the Federal funds rate in the second half of 2020, offering an unbeatable 7.12% yield. They are a tool to stave off the worst effects of inflation, and they are currently a great vehicle for emergency funds.

Withdrawal Scenarios

Before looking at various sample e-fund allocations, consider the following common withdrawal scenarios:

an actual acute emergency, say a roof repair, major surgery, or lawsuit settlement, where you need to liquidate a large portion of it all at once.

income replacement during unemployment, where you have more flexibility to draw from different pools of money at different times.

The following allocation plans seek to cover both scenarios.

Sample Allocations

There is no requirement to keep all of your emergency funds in one type of account. With some creativity its possible to (spiritually) borrow ideas from mortgage backed securities and apply them by carving the e-fund up into “tranches” of different account types in order to take on some additional risk and get a higher blended yield.

Note: There is no free lunch. You are taking on more risk by investing your money outside of an FDIC insured account, and you are being compensated accordingly. In reality, if the US government can’t repay its debt you’re going to have bigger problems than the loss of your principal. As with any investment, understand the risks involved before investing money.

1. Tranching Approach

| Priority | Percentage | Asset | Yield | Months Runway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16% | Checking / Savings Account | .5% | 1 |

| 2 | 16% | Treasury Money Market Fund | 4.23% | 1 |

| 3 | 68% | I bonds | 6.89%* | 4 |

Assumptions: e-fund is 6 months worth of expenses, I bond semi-annual yield extrapolated to APY as of publication.

This gives you a blended rate of return of 5.44%. You can use the bank account trache for immediate, acute expenses up to a months worth. Beyond that you would need to sell some of the treasury money market fund. If you need to withdraw even more you could redeem I bonds in any whole dollar amount, assuming you have held them for 12 months.

This approach offers a balance between maximum liquidity and highest blended yield.

You may blanch at the use of the term tranche which has a negative connotation in popular culture thanks to the mortgage backed securities (MBS) crisis that tanked the global economy in 2008 and their subsequent role in the infamous movie The Big Short. Rest assured that it is part tongue in cheek and part illustrative device.

2. Majority in High Yield Bank Account

| Priority | Percentage | Asset | Yield | Months Runway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16% | Checking / Savings Account | .5% | 1 |

| 2 | 84% | High Yield Bank Account | 4% | 5 |

You could also follow the classic recommendation of putting the majority of your e-fund in bank account. In this configuration, the blended rate comes out to 3.44%. Now, this calculation could be viewed as disingenuous or misleading because the whole e-fund could be stored in a “high yield” bank account, however some of these accounts do not have checkwriting or debit card capabilities. If you use a bank that allows those features or requires use of them to satisfy earning requirements, use 4% as your comparison yield.

This approach offers the maximum amount of liquidity and the lowest blended yield.

3. Majority in I Bonds

| Priority | Percentage | Asset | Yield | Months Runway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16% | Checking / Savings Account | .5% | 1 |

| 2 | 84% | I bonds | 6.89% | 5 |

Another possibility is just buying enough I bonds to satisfy your emergency fund requirements. Unsurprisingly, keeping the vast majority of your e-fund in I bonds produces the highest blended rate 5.87%.

This is the least liquid option; each bond has a 1 year lockout period, including an new bonds purchased to replenish any withdrawals. However it does offer the highest blended yield of any scenario.

This example assumes 16% of the fund is stored in a bank account to prevent redeeming I bonds for smaller emergencies.

Also keep in mind that if your emergency fund is more than $10,000 it will take multiple years to transition to I bonds; you will need to hold the equivalent amount of cash elsewhere while you wait for the 1 year lockout period per bond.

Considerations for 2023

The scenario #1 was more interesting in May 2022 when I bonds yielded 9.62%, resulting in a blended rate of 7.3%, far beyond the paltry .6% offered by Ally during the same time period.

With regional banks and credit unions offering 4% and taking into consideration the current I bond rates / sample allocation as shown in the chart, it may be less enticing.

Its worth mentioning that tranching your emergency fund as described means you only need accounts at your everyday bank, TreasuryDirect, and your broker. In this way you can avoid the hassle involved with changing banks as you chase yield.

Wrapping Up

The reality of the situation is that you’re going to lose some purchasing power no matter what. There is no stable value instrument that offers inflation indexed yields other I bonds; and even then you can only buy $10,000 a year and they underperform inflation post-tax.

The ultimate goal for an emergency fund is to keep up with rate of inflation while remaining stable and liquid. This is a tall order, so work with the tools available to find a happy medium between risk, yield, and liquidity. Experiment with allocations according to your personal preference, your requirements will vary and this article simply seeks to illustrate the possibilities.